Americans and Israelis who hate the new nuclear agreement with Iran are already focusing on one part in particular: It doesn’t authorize snap, no-notice inspections of all locations. Israel’s hard-right Education Minister Naftali Bennett claims the accord is a “farce” because “in order to go and make an inspection, you have to notify the Iranians 24 days in advance.”

This is not exactly right, but close enough. (Iran’s declared nuclear sites will be under continuous monitoring. If the International Atomic Energy Agency wants to inspect a non-declared site and Iran refuses, Iran has 14 days to convince the IAEA it’s doing nothing wrong without providing access. If it can’t, the commission governing the agreement has seven days to vote on whether to force Iran to provide access, and if it does Iran has three more days to comply. The exact procedure is established in paragraphs 74-78 of the agreement text.)

For people unfamiliar with the history of arms control generally and in the Middle East in particular, this might seem like a bad deal. If Iran doesn’t have anything to hide, why wouldn’t it allow the IAEA to go anywhere at anytime?

The answer is twofold:

First, all countries have things they legitimately want to hide, such as conventional military secrets and the security procedures of their leaders.

Second, during the 1990s the U.S. demonstrated with Iraq that it would routinely abuse the weapons inspections process in order to uncover such legitimate secrets — and use them to target the Iraqi military and try to overthrow the Iraqi government.

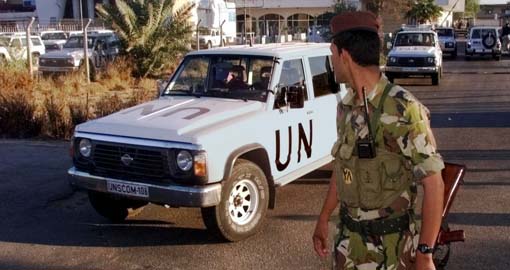

The United Nations Special Commission, or UNSCOM, was created in 1991 after the Gulf War to verify that Iraq no longer had any nuclear, chemical or biological weapons programs. And though we now know Iraq was essentially disarmed within several years, UNSCOM stayed in business thanks to a combination of Iraq’s lies about its past WMD activities and a U.S. desire to maintain harsh economic sanctions justified by Iraq’s purported WMD.

By the mid-1990s, Iraq claimed that the U.S. was using UNSCOM as cover for espionage aimed at things that had nothing to do with WMD, such as Saddam Hussein’s location. While the U.S. strenuously denied this for years, it turned out to be true. Moreover, former UNSCOM inspector Scott Ritter contends that the U.S. attempted to manipulate UNSCOM so that it could be used as a tool in an attempted coup against Saddam Hussein organized by the U.S. in 1996.

Iraq acted at the time just as the U.S. would if the Organization for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons had been infiltrated with “inspectors” who wanted to assassinate Bill Clinton and then showed up at the White House. For instance, when Clinton bombed Iraq in Operation Desert Fox in 1998, one of the justifications he gave was that Iraq had “shut off [UNSCOM] access to the headquarters of its ruling party.” The CIA later discovered that Saddam had in fact been at the party headquarters when UNSCOM arrived, and had stopped UNSCOM from entering “to prevent the inspectors from knowing his whereabouts, not because he had something to hide.”

Moreover, the U.S. made extensive use of UNSCOM to target Iraq for bombing campaigns. According to Ritter, toward the beginning of the UNSCOM process CIA agents who were part of the inspection team used GPS to record the precise location of sites used for Iraqi military manufacturing — sites that soon afterwards were struck by U.S. cruise missiles. And as the Washington Post reported and the U.S. Air Force later confirmed, the U.S. used UNSCOM’s data to choose targets for Operation Desert Fox, including many that had nothing to do with Iraq’s purported WMD programs. (In retrospect, what’s remarkable about the history of UNSCOM isn’t Iraq’s real but largely minor obstruction, but its extensive cooperation. Ritter remembers inspections when he was “looking through a logbook dealing with presidential security, such as how they arranged convoys” and at Iraqi intelligence headquarters “examining the darkest secrets of how they recruited agents and how they paid them.”)

So Iran’s refusal to allow snap inspections doesn’t prove that its leadership wants to conceal a nuclear weapons program. It more likely suggests that its leadership simply wants to preserve its conventional military and personally remain alive. This is especially plausible given that Iran’s Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei was crippled in an 1981 assassination attempt carried by out the Mujahedeen-e-Khalq, or MEK, an Iranian opposition organization that supported Iraq during the 1980s Iran-Iraq war. Making this even more threatening from Iran’s perspective, the MEK is now beloved by much of the U.S. foreign policy elite, and has apparently killed numerous Iranian nuclear scientists with Israeli funding and training.

And if you hope Iran may simply be unaware of our use of arms control as cover for spying, think again: an Iranian spy in Baghdad at the time actually discovered what we were doing before even the UK, our closest ally. (Wonderfully enough, the UK only found out when it intercepted the Iranian spy’s message back to Tehran.)

So while Iran’s recalcitrance may make the U.S. and Israel unhappy, it’s largely the fruit of our own poisoned tree. They will never accept the conditions we imposed on Iraq, and any neutral observer would agree they’d be fools to do so.

By Jon Schwarz, firstlook.org